Tekla Maria Kanari

(1898 - 1981)

Tekla Kanari (left) and John Kanari, circa

1940s.

Finlander Tekla Maria Kanari never planned to live in faraway Alaska for much of her adult life. She was born in the farming village of Kustavi near Turku, Finland, where her homeland had been an autonomously administered region of Imperial Russia since 1809. As a young woman, she witnessed the establishment of Finland as a new nation state after the Bolshevik Revolution transformed much of the Russian Empire into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). During WWI, Finland's national hero, Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, fought with distinction German and Austrian adversaries for Russian Tsar Nichols II along the Austrian and Romanian Fronts—even winning the coveted Order of St. George. Never-the-less, he was determined that Finland would not become a Republic of the USSR after its creation in 1918. A brief civil war between the Red Army and the Mannerheim-led White Army ensued and the latter won—insuring that Finland would become an independent nation state for the first time in its history.

With the advent of the world-wide depression that began in in late 1929, Tekla's husband, John, immigrated to the United States. At his departure, he told Tekla that he would send for her after he established a stable means of livelihood. Immigrations records show that John Kanari applied for a 'Petition for Naturalization' in Nome, Alaska in 1930. By 1932, John Kanari had become a gold miner in the Kougarok region north of Nome, Alaska, where he partnered with two other Finlanders, Al Carey (aka Alfred Karje-Penttila), and Hector Laurin. Carey, Laurin, and Kanari shared profits and claims of their initial mining operations. Additional claims were staked and developed in 1936 on the Kougarok River by the incorporated partnership known as Kanari, Laurin and Carey, Inc. In official territorial records, the mine development is referred to as 'hydraulic'. The number of employees was six.

It is not entirely clear whether the lack of correspondence between John and Tekla was due to the unreliability of surface mail or electronic methods of communication (telegraph or telephone) or just due to neglect by the former; but after not receiving any instructions from her husband, Tekla left Finland in 1934, determined to find John. Tekla arrived at Ellis Island in New York, and after completing her immigration paperwork, began work in Brooklyn. Subsequently, she made her way across the United States, where she was employed as a maid in hotels, as a waitress in coffee houses, and any other labor she could find. She eventually discovered through research with the U.S. Customs and Immigration Service that John had resided, at least during the winter, in Nome, Alaska.

In 1936, Tekla bought an Alaska Steamship ticket bound for Alaska and by mid-summer had reached Nome. Upon reaching her final destination, she promptly applied for a 'Petition for Naturalization' to receive eventual U.S. citizenship. No matter what she would face in her future, she was here to stay. Tekla was determined to be an American citizen.

Tekla was finally rejoined with her husband John and the couple, along with Al Carey, collectively formed Trinity Mining Company (TMC) in 1937—not to be confused with the Trinity Mining Company created by AMHF inductee William Ewing in 1915. The previous partner to Kanari, Hector Laurin, rejoined with his brother's mine outfit on Macklin Creek. TMC operated out of Trinity Creek, Alaska in the Kougarok district, where regular postal services was established. Their operations were in the remote part the northern Seward Peninsula in a classic frontier mining camp setting 75 miles north of Nome. Mining took place from April to October. When the ground froze up and the water froze, the camp crew demobbed the operation and the Kanari couple moved to Nome for the winter.

For twenty (20) years, TMC was one of the most successful small scale gold mining operations in the history of the Kougarok Mining district, which was then administered as a part of the Cape Nome Mining District. The operations of TMC continued in earnest by Al Carey and John and Tekla Kanari, along with a half dozen employees. What made TMC succeed was that the main driver of the partnership was shared equally by John and Tekla. John and Tekla were hard workers—even ambitious.

Whereas John did much of the 'caterpillar mining,' Tekla worked on equipment; operated water giants, bought groceries, hauled in supplies, made most of the clean-ups, and managed the books. TMC's consistent success story relied much on both Tekla's brawn but especially her brains. Operating in the remote camp did have it's challenges. One 1948 correspondence deals with the need to repair a fuel pump, a starting engine clutch and other damaged parts at the Caterpillar division of Northern Commercial Company (NCC) in Nome. John and Tekla Kanari thanked the NCC in advance for assisting in the 'mechanical emergency.'

Most provisions need by the TMC that came out of Nome were sometimes shipped to Shismaref on the coast or Candle to the east. From either site, TMC personnel would freight the foodstuffs, mining equipment, and spare parts back to the Kougarok usually by 'Cat Train'. Examination of mine records during 1936 and 1948 suggest other Finnish nationals were working for the TMC, including Otto Lahikaimen and Enok Myutthi. Like so many mining camps occupied by Scandinavians, the Trinity Mining Company featured a well-furnished Finnish sauna.

Abandoned building that served as a bunk house of Trinity Mining Company.

Photo Credit: Elizabeth Riffey

Betsy's sons Kris and Kevin stand next to the Kanari sauna at Trinity Camp. Both images undated. .

Photo Credit: Elizabeth Riffey

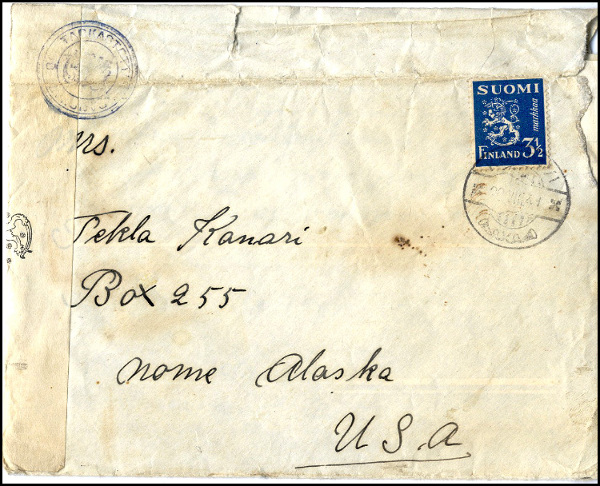

During her years of mining in in the Kougarok, Tekla sent numerous money orders and care packages from her new home to friends and family in war-torn Finland, which experienced extreme poverty during WWII and at least for a time during the post war years of the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Soviet Union, Germany, Poland, Yugoslavia, and Finland experienced the largest human losses as a percentage of the total population of any nations engaged in the European theatre of WWII. Tekla's activism began in late 1940, after the termination of the Russo-Finnish war of 1939-1940. She began to wire-transfer funds to friends and relatives in the war-torn country in 1940. During Finland's 'first war', at great cost, the USSR annexed Karelia and adjacent areas. Casualties on the Finnish side were equally high. On June 21, 1941, Nazi Germany and its allies attacked the Soviet Union. Finland allied with Germany in order to take back Karelia and other territories lost to the USSR in 1940. Several letters from Finland (translated by Kristina Ahlnas in Fairbanks) to Tekla illustrate Tekla's involvement in helping those in need. Excerpts from a letter written by Tyyne Enberg Anabainen, Tekla's brother, on August 16th, 1941, poignantly describes the situation in war-torn Finland at the beginning of Finland's 'second war'. Tyyne, who was not eligible for military service, continued to run the family farm. Excerpts of the letter, written in Finnish, follows:

My Dear Sister!

From far away with many greetings. Have you seen the letter that I sent on the same day that the war started for Finland again on June 22, 1941? This life is awful when so many already have not returned from the front, where both old men and youngsters are dying together in those killing fields. Death is waiting there every moment. It is good that Arne (another brother of Teklas) has not yet been wounded. Here in Kustavi, an old farmer has just lost his 3rd son. He lost the 1st and 2nd sons in the first war. Now he has no more sons Thank you so much for the money (1,440 marks). Olya also thanks you for the money sent to her. And Ina is screaming at the top of her lungs thanking you for the package she received—so loud that everyone in the village hears it!..........Before Arne left for the front, we repaired the barn. Inside the barn, everything has been rebuilt. And maybe I have found me a helper for this winter; a big man named Veeijo. . . Father is feeling well but mother feels very old. Maybe both of them will stay with us this winter . . . But now I must cut hay to feed the cows this winter. I will soon harvest the potatoes. And we also have 29 sheep to feed. So I must return to work. Let's wish for better times.

Good Bye Sister!

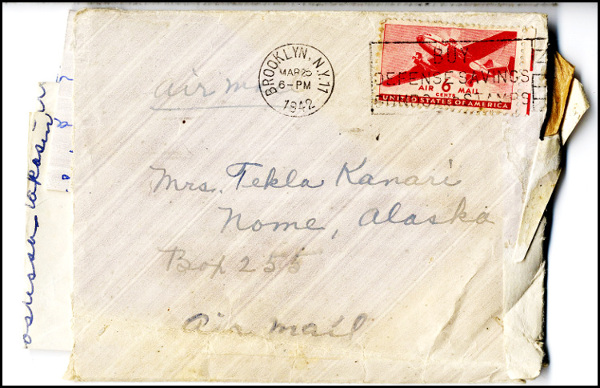

For several years before, during, and after WWII, Tekla provided for food and other materials to friends and relatives in Finland through agents in Brooklyn, New York. Whereas Tekla could wire funds directly to Finland from Nome, to ship materials, she had to employ assistance from agents in Brooklyn, who would acquire the desired foodstuffs and equipment and provide estimates of costs to Tekla. Upon mutual agreement of terms, Tekla would then wire transfer funds from Nome to the Brooklyn-based agents. The materials were then loaded onto freighters bound for neutral Ireland, neutral Sweden, or Finland. A letter postmarked November 24th, 1942, and written in Finnish was sent to Tekla from Elizabeth Bloomquist:

Good day, Mrs. Kanari:

Thank you for the letter written some time ago. Our little boy liked the pictures of school boys in Nome that you sent me. I am mailing you the NY newspaper that describes the Finnish care efforts, which of course you are involved. For your interest, a 15 pound package you inquired about would cost $5.00 to man named Veeijo. Your last shipment was sent aboard the SS Kroner. It included 700 pounds of sugar, an electric refrigerator, and several bulk dried food types. One cannot send packages anymore without inspection by authorities who search for war materials. But some materials can be sent by air. My 18 year old daughter Ethel is making $45/week in an airship factory. That is very good pay for such a young girl! My husband believes he will be soon be drafted. He is 44 but still eligible for the draft. Can you send me an Alaskan newspaper? My 14 year old boy wants to travel to Alaska, because of all the girls there. Ha! Ha!! . . . Is there much defense work in Nome? I just visited the Brooklyn naval yards and the people there are making a lot of money—more than $100/week! I must go now.

Good bye,

Elizabeth Bloomquist

Although remote, the Kougarok district where Trinity Mining Company (TMC) operated experienced the same competition with respect to holding mining claims as other mining jurisdictions in the Alaska Territory. Mine entrepreneur Sam Godfrey, who in 1937 partnered with AMHF inductee Johnny McGinn to construct a 3 cubic foot bucketline gold dredge in the Kougarok district, over staked claims held by Trinity Mining Company in the Kougarok district. The over staking occurred during World War II, when the requirement to do annual assessment work on mining claims was suspended by the Federal Government. After WWII, John Kanari, who served in the Territorial Guard during the war, returned to Nome to mine in the Kougarok district. Much to his surprise and disappointment, he discovered that over staking of all of Trinity's claims by Godfrey had occurred during the war years.

In order to regain the TMC claims, John and Tekla Kanari filed their intention to hold mining claims, citing Public Law 735-80th Congress, Chapter 595-2nd Session (H.R. 6239). This congressional enactment allowed for the suspension of annual assessment work by miners affected by war time conditions until July 1, 1948—extended until July1, 1949. Included in Kanari's filings were restoration of the rights of 14 mining claims in the vicinity of the Trinity Creek, a tributary of the Kougarok River. Sam Godfrey's buckeline gold dredge was eventually sold to Nicholas and Evinda Tweet; aka N.B. Tweet and Sons, which operated the dredge to this day—the only bucketline stacker gold dredge still operating in Alaska.

John Kanari died of a massive heart attack at the TMC mine site in 1954, following Al Carey's death three years previously. Tekla continued to mine and prospect in the Kougarok district for years on her own; albeit at a much smaller scale. Her close friend Hazel Le Compte related in a May 12th, 1955 letter:

I suppose that you will be at Taylor Creek getting your assessment work done and your mine plans completed. Have you sold any of that oil at Dahl Creek? I hope that you did. I'm glad that your luck has changed. You are a very clever business woman.

In 1959, Tekla married Herman Gustafson, a longtime gold miner who operated a placer gold operation on Oregon Creek near Nome. In the early 1960s, Tekla sold all of the assets of Trinity Mining Company and both Herman and Tekla moved to Seattle. Tekla's departure from the mining business not only coincided with important new changes in her personnel life and her age (she was 62 when she married Herman) but also a time when placer gold mining had declined significantly from previous levels. The chief culprit for this decline was the fixed price of gold at $35/ounce, where it had remained since 1934. In a speech before the U.S. Senate in 1965, Alaska Senator Ernest Gruening stated:

Because of the fixed price of gold, no industry in the history of this country has ever been the target of greater discriminatory practices and abusive executive power than gold mining. Costs for gold miners have risen more than 150 percent since the 1934 price freeze was imposed.

Gruening went on to relate how the loss of gold-mining jobs in rural communities like Nome, Fairbanks, McGrath and in other regions had caused a loss of economic diversity in rural Alaska. Gruening managed to obtain a number of senators as co-signatures on a bill designed to either remove the gold price control or provide for a gold price incentive program. His bill failed. Placer gold mining in Alaska would not be revived until the Presidential administration of Richard Nixon removed the Roosevelt era price control on the gold price in the early 1970s.

Tekla and Herman stayed in touch with their friends in Alaska and hosted many 'Nomeites' in their Seattle home. Tekla Maria (Kanari) Gustafson passed away in Seattle in 1981 of unknown causes.

Tekla's life story is one of a European immigrant's search for a lost husband, reestablishment of life in a brave new world, success in the mining business in a remote part of the Alaskan frontier, and care for family members and friends she left behind in war-torn Finland. Her courage, strength, perseverance and basic character has earned her a place in the Alaska Mining Hall of Fame. And by honoring Tekla, we also recognize her first husband John, Al Carey and other miners of Finnish origin like AMHF inductees Gus Uotila and Toivo Rosander for their important historic contributions to the Alaska Mining industry.

Letter from Tynne Enberg Anabainen (Tekla's brother) on August 16th, 1941 from Turku, Finland

Letter from Brooklyn resident Elizabeth Bloomquist, one of Tekla's agents for sending food and care package materials to Finland, dated November 24th, 1942.

Written by Thomas Bundtzen and Elizabeth Riffey, October, 2018.

Reviewed by Paul Glavinovich

The AMHF thanks Kristina Ahlnas for translating several of Tekla's letters and Douglas Tweet for clarification of mine-related activities of the Trinity Mining Company.

SOURCES

Greening, Ernest, 1965, End Discriminatory Price Controls on Gold: The Nome Nugget, 1965

Letter from Edward Bloomquist of Brooklyn New York to Mrs. Tekla Kanari, Nome Alaska dated May 27th, 1941, in Finnish Language, 2 pages.

Letter from Tyyne Enberg Anabainen (Tekla's brother) to Tekla Kanari, Nome Alaska on August 15th, 1941

Letter from Elizabeth Bloomquist of Brooklyn New York to Mrs. Tekla Kanari, Nome Alaska dated March 25th, 1942 (in Finnish Language), 5 pages.

Letter from Charles D. Jones (Attorney) to John Kanari, of Nome, Alaska dated June 1, 1946 concerning the Over staking of Kanari's (Trinity Mining Company) placer estate by Sam Godfrey, 1 page.

Duffield, T.C., 1948 and 1949, Intention to Hold Mining Claims (2 documents): Legal documents filed by John Kanari using Public Law 735-80th Congress.

Letter from Kati Ingala of Suquamish, Washington to John and Tekla Kanari, dated January 18th, 1950; in the Finnish Language, 2 pages.

Letter from Hazel Le Compte of San Francisco, California to Mrs.Tekla Kanari, of Nome, Alaska dated June 12th, 1955, in English, 1 page.

Correspondence from Connie Erickson of Missoula, Montana to Mrs. Herman Gustafson dated June 6th, 1959 (in English), 4 pages.

'Kaukainen vieras Kalajoella' Article about Al Carey (Alfred Karje-Penttila) in Finnish, 1948. Published in in Brooklyn, New York publication.

Holdsworth, P.R., 1953, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1952: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 62.

Holdsworth, P.R. 1955, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1954: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 62. (records indicate that Trinity Mining only operated in 1953—not 1954—due to the death of John Kanari)

Holdsworth, P.R., 1957, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1956: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 62. (records do not indicate no production activity for either TMC or Tekla Kanari)

Saarela, L. H., 1951, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1950: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 53.

Stewart, B.D., 1937, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1936: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 62.

Stewart, B.D., 1939, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1938: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 58.

Stewart, B.D., 1941, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1940: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 89.

Stewart, B.D., 1947, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1946: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 46.

Stewart, B.D., 1949, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Mines to the Governor for 1948: Alaska Territorial Department of Mines, page 46.

U.S. Immigration Service Alaska Archives Summary, for John Kanari (Case 567) and Tekla Maria Kanari (Case 638).